On December 12, 1901, Guglielmo Marconi sent the first radio transmission across the Atlantic Ocean. This historic moment marked the dawn of a new era of wireless communication. The transmitter he used was designed by Sir John Ambrose Fleming. This demonstration proved that radio waves could travel beyond the line of sight, bending with the curvature of the Earth. Imagine how Fleming must have felt, knowing the transmitter he built had accomplished this remarkable feat. Even after more than 120 years, it still seems awe-inspiring. What better way to relive that excitement than by building your own transmitter and sending a signal across the vast open ocean?

Designing a Transmitter

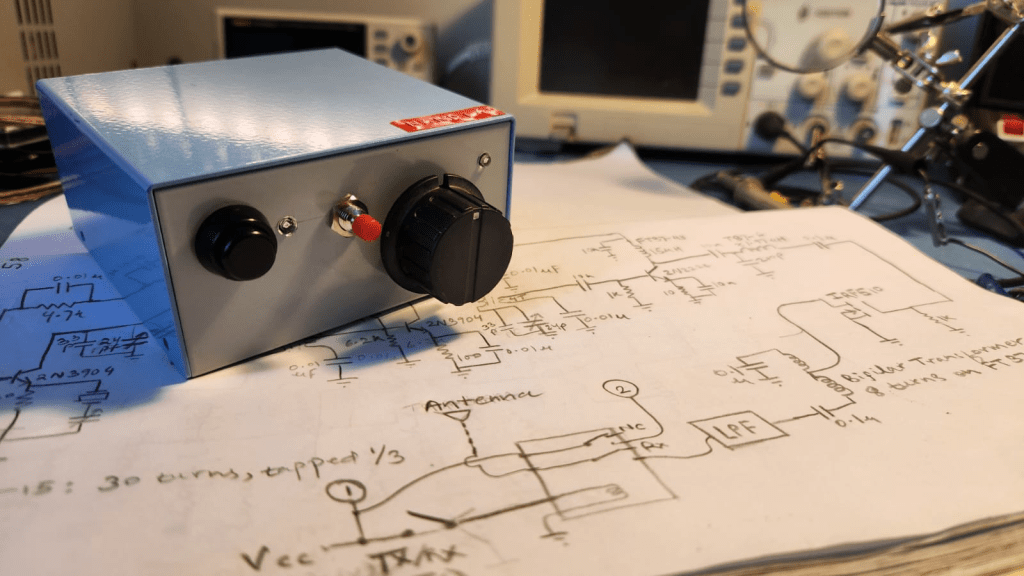

I began working on a CW (Continuous Wave) transmitter inspired by the book “Crystal Sets to Sideband” written by my dear friend Frank Harris (K0IYE). In general, CW transmitters are simple to build and understand. You slosh electrons back and forth at just the right frequency, and you will generate a form of invisible light that can travel thousands of kilometers. I’m referring to electromagnetic waves, of course! CW doesn’t transmit voice; it is just an unmodulated carrier wave. Communication happens through Morse code.

I built the oscillator and buffer amp exactly as described in Frank’s book. The oscillator is a Butler-type oscillator, which is a rather unusual choice. Most circuits use a Hartley or Colpitts oscillator, but Frank mentioned that the Butler oscillator has little start-up drift.

The buffer amp bumps the output of the oscillator to about 50 mW and adds a layer of separation between the oscillator and the subsequent stages. This helps keep the load on the oscillator as light as possible.

I didn’t have the same transistor Frank was using in the final PA (Power Amp), so I took it as an opportunity to design the rest of the circuit on my own. I decided to use the ubiquitous IRF510 MOSFET, which I had in abundance. After experimenting with the IRF510, I realized I would need at least 200-300 mW of drive to generate 5W+ of RF power, which is what I was aiming for. I realized my puny buffer amp didn’t have the juice to do it.

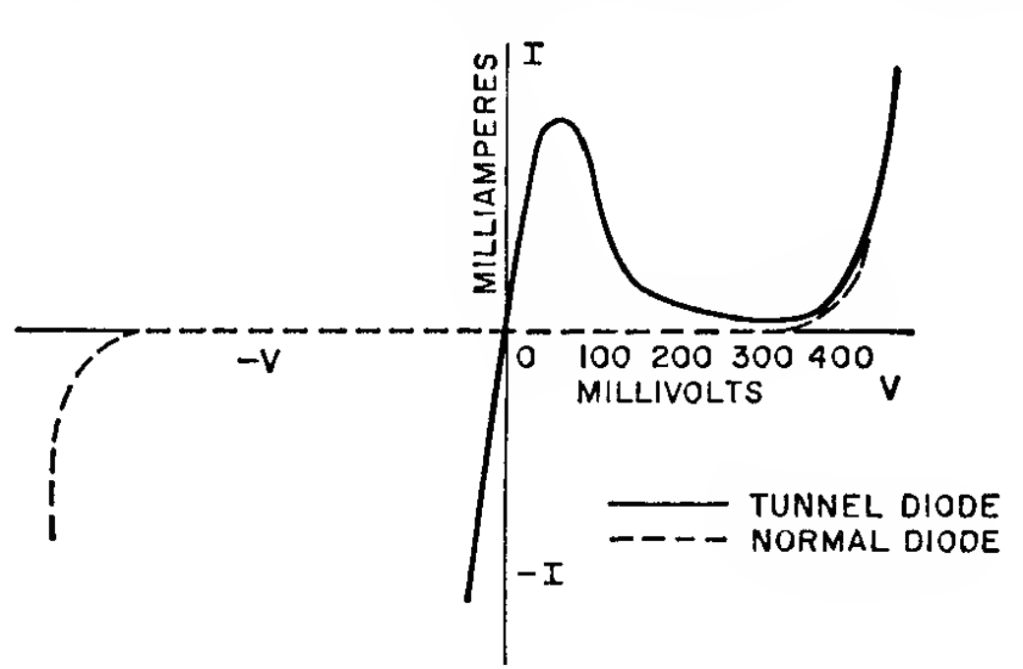

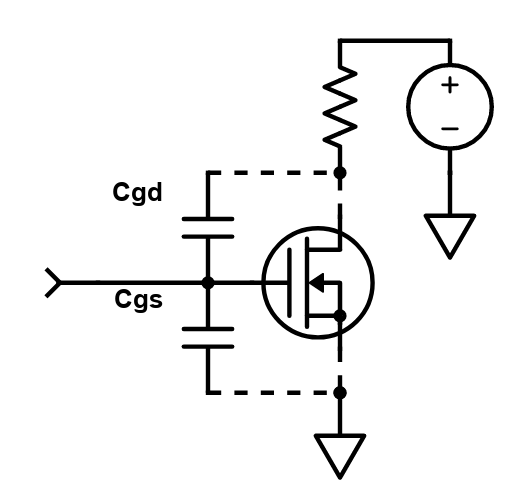

But aren’t MOSFETs voltage-driven devices with sky-high input impedance? Yes, that’s true when you look at them from a DC perspective. But the high impedance goes out the window once you start dealing with high-frequency AC signals. The gate is essentially like a capacitor. Depending on the frequency (and other factors which I’ll discuss), its impedance changes. So, I had to design another “driver” amp stage to drive the IRF510.

I experimented with several types of driver amp circuits. Some of the ones that I tried to design on my own didn’t work so well. I finally settled on a design I found in the book “Experimental Methods in RF Design” by Wes Hayward et al. It produces about 300-400 mW with an efficiency of about 70% (typical for Class C). This is more than enough to satisfy the IRF510.

What makes the IRF510 interesting is that it was made by International Rectifier in the 1970s for the automotive industry. It was used to replace clunky electromechanical relays being used in blinkers and dimmers. Who would’ve guessed that decades later, it would become a favorite among amateur radio builders, operating at frequencies far beyond what it was originally designed for!

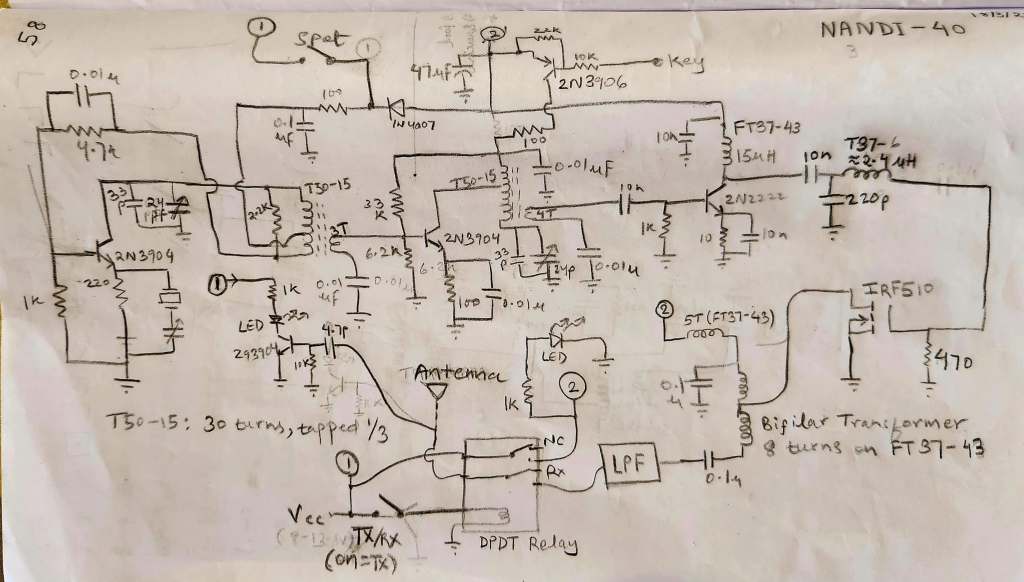

The Full Circuit

The Gate Capacitance Paradox

Connecting the driver stage to the power amp was a challenge. In RF circuits, matching one stage to another often involves some sort of matching network. I’ve talked about this in my blog post about impedance matching and archery.

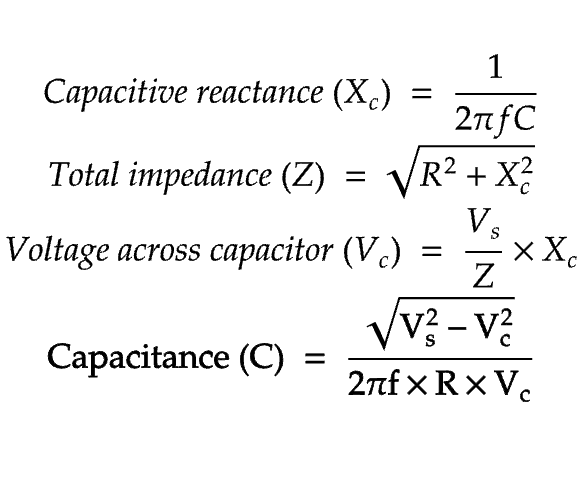

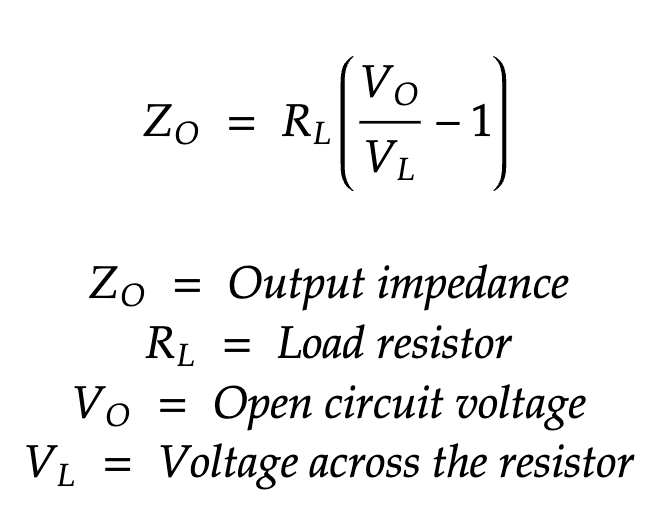

I tried to be methodical about designing the matching network. I started off by determining the output impedance of the driver stage by loading it with different resistors and recording the voltages. Here is the formula:

This formula is useful when driving the amp without a load is undesired. However, if the open circuit voltage can be measured, this formula could be used:

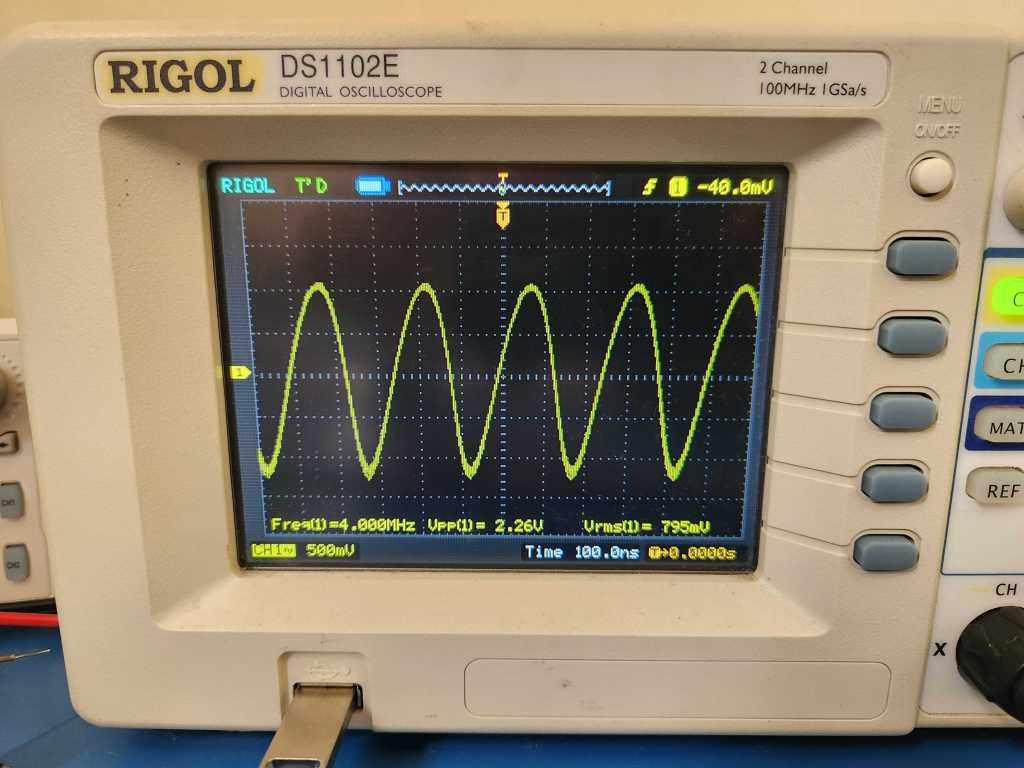

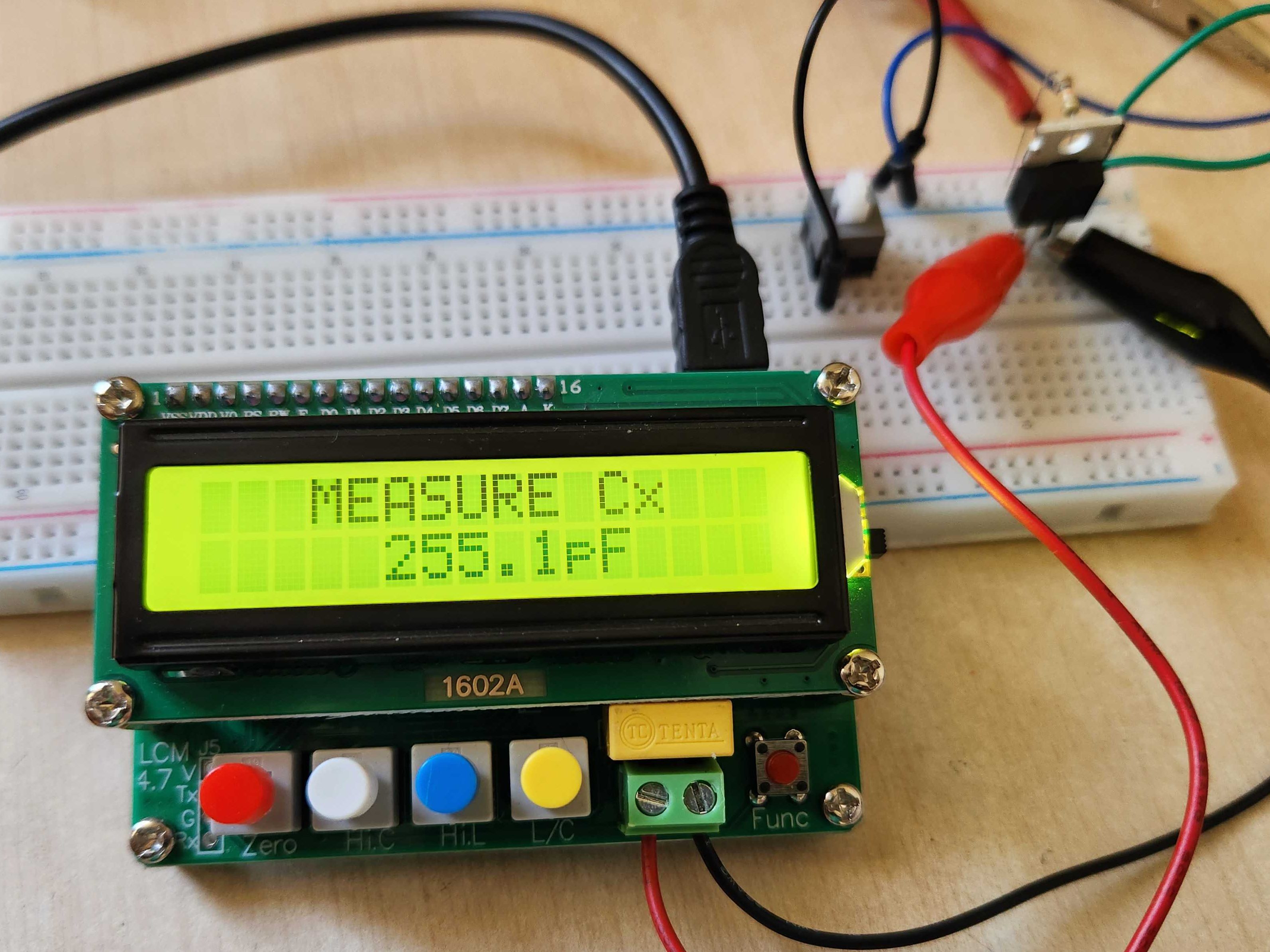

These equations are not magical; they could easily be derived using Ohm’s law and the basic voltage divider equation. I determined the input impedance of the IRF510 (about 220 ohms) by using a signal generator and measuring the voltage across the gate with an oscilloscope. The output impedance of the signal generator and the input impedance of the IRF510 form a voltage divider. The voltage divider formula can be used to determine the unknown input impedance.

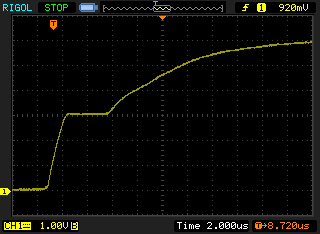

I discovered that the input impedance of a MOSFET isn’t fixed. It is dynamic and changes with the drive voltage. If the drive voltage is below the IRF510’s gate threshold voltage Vgs(th), its impedance appears quite high. Once the voltage goes above the threshold, it starts dropping. After some speculation, I came to the conclusion that this is the result of the Miller effect. I’ve encountered this phenomenon in another experiment in the past.

“In electronics, the Miller effect accounts for the increase in the equivalent input capacitance of an inverting voltage amplifier due to amplification of the effect of capacitance between the input and output terminals.“

So, when the capacitance increases, the capacitive reactance decreases, since they are inversely related. This reduces the effective impedance of the gate. Well, I guess that explains the mystery.

I initially tried designing an LC L-match to match the output of the driver to the input of the MOSFET. But despite careful calculations, the PA didn’t perform well. I also experimented with transformer coupling using a 10:3 turns ratio, but that approach didn’t yield good results either.

Eventually, I settled on an L-match configuration with the shunt element placed on the driver side, which has lower impedance than the MOSFET’s input. This goes against convention, as the shunt element is typically placed on the higher impedance side. Yet, to my surprise, this unconventional setup worked significantly better. I think this is because this LC network forms a low-pass filter, which removes frequencies above a certain cut-off frequency. In my case, the values I’ve used would have a cut-off near 7 MHz. However, this filter could be tweaked to improve performance. It seems these values are not too critical. If you reduce the cut-off frequency, you would have a lower voltage at the MOSFET’s gate.

I’m not aiming for maximum power transfer with this matching network. Instead, I’m using a low-pass filter to ensure sufficient voltage swing—around 10V at the MOSFET gate—to drive it into saturation without exceeding its ±20V maximum gate rating.

The Gate Resistor’s Little Secret

I have a 470-ohm resistor connected to the gate of the MOSFET to provide a ground reference. I initially used a large 1 megaohm resistor to reduce resistive loading on the driver stage, but the transmitter performed poorly.

After some experimentation, I came to suspect that this resistor plays another important, and less obvious role: discharging the gate-to-source capacitance (Cgs) between RF pulses. This helps ensure the MOSFET remains off during the portions of the cycle outside its conduction angle. At 7 MHz, the period is just 142 nanoseconds. If the resistor is too large, Cgs doesn’t fully discharge between pulses. After experimentation, I settled on a 470-ohm resistor. A 1K resistor also worked well, but going much higher started to degrade the results.

Transmit, Receive, and Keying

The transmitter has a transmit/receive (Tx/Rx) switch. While it doesn’t have a built-in receiver, an external receiver can be connected and used alongside it. For Tx/Rx switching, I use a small DPDT relay. In receive mode, the relay completely cuts power to the transmitter to avoid interference.

I also added a “spot” button that can be pressed while in receive mode. This powers up just the oscillator, allowing me to hear its tone on the receiver. This lets me check if I’m in tune with another operator’s CW signal, kind of like tuning a guitar to match pitch.

In transmit mode, the oscillator runs continuously. Pressing the key activates the buffer amplifier stage using a PNP transistor. Once enabled, the buffer amp passes the oscillator signal to the subsequent stages. This approach ensures that the small PNP transistor isn’t burdened with the high current demands of the driver and power amplifier. Instead, it simply triggers the buffer amp.

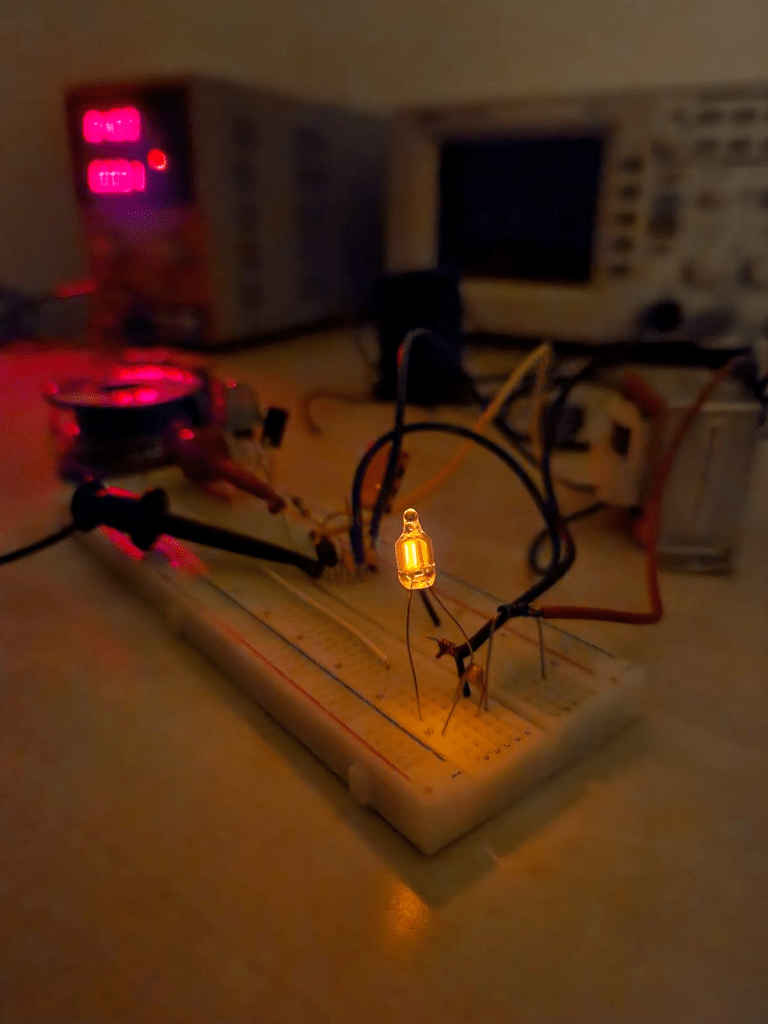

I also added two LEDs for visual feedback. One LED indicates when the transmitter is in Tx mode. The second LED lights up when the transmitter is keyed, specifically, when an RF signal is being fed into the antenna. It helps verify that everything is working as expected. If this LED doesn’t light up, it means no RF is reaching the antenna, and something’s wrong. To minimize the current draw from the RF path, I used a transistor to drive this LED.

Cleaning the Output

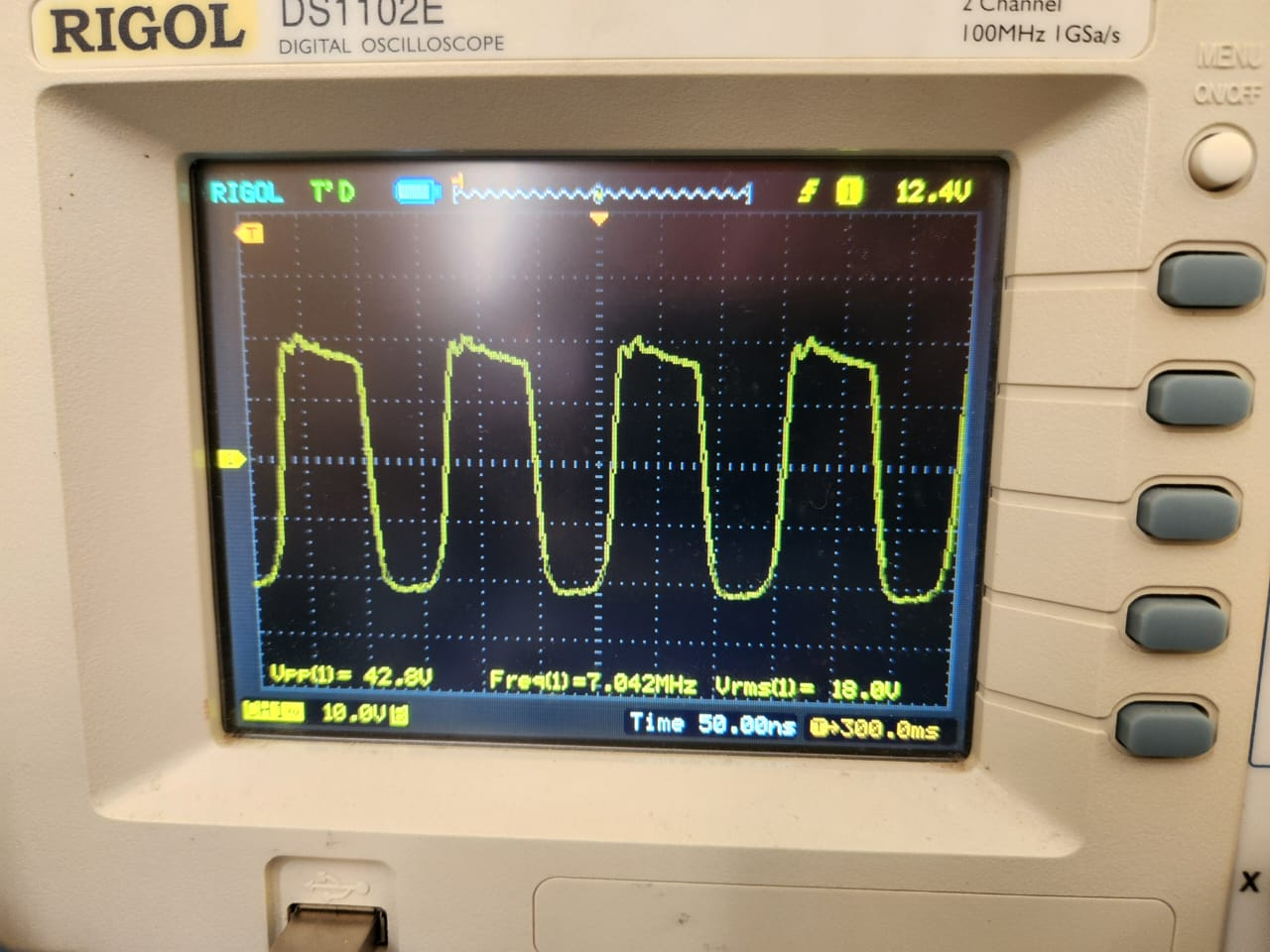

Unlike Marconi, we can’t use a noisy spark transmitter on the air. The output from the PA was noisy and full of harmonics. I used a low-pass filter (LPF) to clean it up.

I tried designing a 5-element filter on my own. While it worked, its filtering wasn’t as strong as I would have liked. I did learn about filter design and Smith charts in the process.

In the end, I settled on a 7-element 40m LPF kit from QRPLabs that was cheaper than buying the components individually. It worked really well.

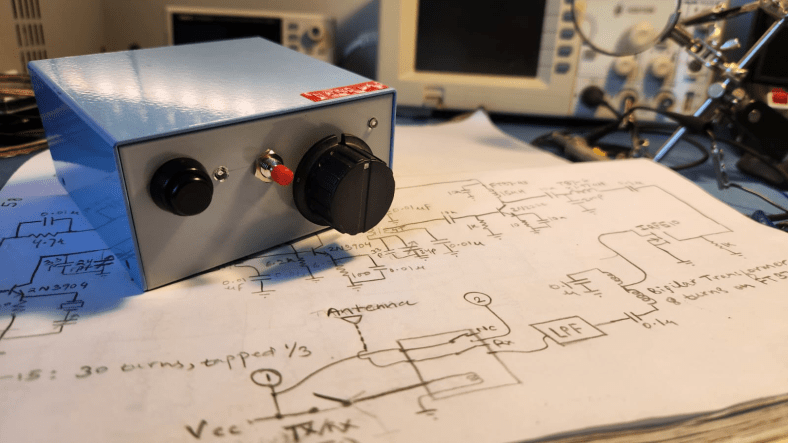

The Finished Transmitter

I named the finished transmitter “Nandi-40” because I live near Nandi Hills, and “40” refers to the 40m wavelength of the radio waves it produces. With a fully charged 12 V battery, it puts out about 10-12 watts of RF energy. With a 9V supply, it delivers about 4 watts. It definitely exceeded my design goals. Now it is time to see if it can cross the ocean like Fleming’s transmitter!

Transoceanic Transmission

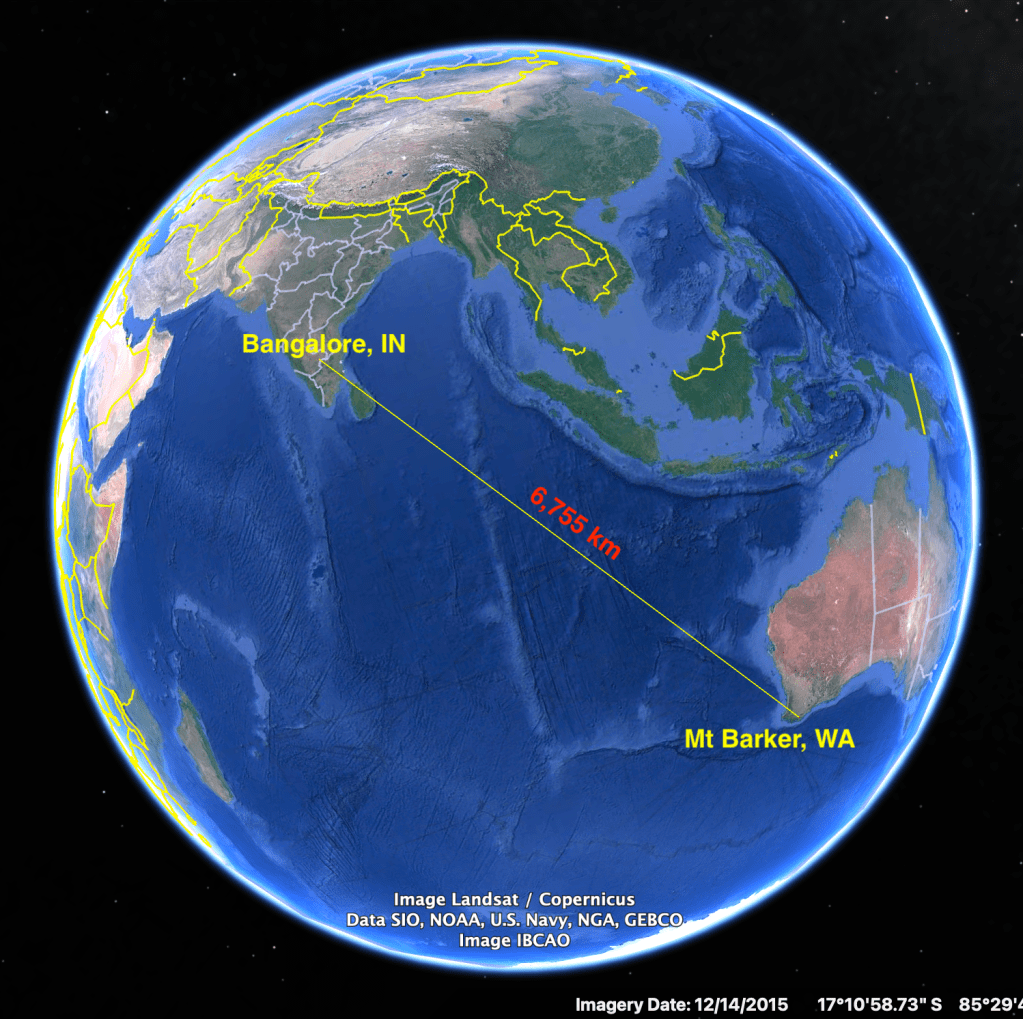

I waited for good propagation on the 40-meter band. As the sun dipped below the horizon and conditions aligned, I tuned in to a web-SDR receiver in Mt. Barker, Australia. These Australian receivers have a very low noise floor. If the Nandi-40’s automotive MOSFET was indeed stirring the ether, there was a good chance I might hear it.

I keyed the letter “S” in Morse code, three simple dots, just like Marconi did. And to my amazement, those three little blips rose above the noise floor in Australia, nearly 6,700 kilometers away!

Sure, long-distance communication is nothing new in the world of amateur radio. But there’s something uniquely satisfying and almost magical about doing it with a transmitter you built yourself.